A. Luxx Mishou

Jack the Ripper was not England’s first serial killer, this title is often attributed to Mary Ann Cotton, who was executed in 1873 for poisoning over a dozen people (Flanders 415).[i] Jack the Ripper was not the only Victorian serial killer to target prostitutes; Dr. Thomas Neill Cream murdered nine people between 1877 and 1892, eight of them women, and four of them confirmed London prostitutes (McLaren). The violence attributed to Jack the Ripper was gruesome, but not singular; as early as 1811 the mysterious murders of the Marrs household attracted “visitors [who] traipsed through the gore-spattered rooms” where fragments of the apprentice’s brains were found on the ceiling (Flanders 3-5). Sensational reporting of grisly murders did not originate with Ripper journalism; Richard D. Altick writes of “a pair of mysterious, murderous attacks in and near London in the summer of 1861, covered by the energetic press with almost unprecedented thoroughness and excitement” that began what Altick calls the “Age of Sensation” in the 1860s (4). Lucy Worsley supports this idea by noting that in the beginning of the nineteenth century “the British enjoyed and consumed the idea of murder” (2). Jack the Ripper is but one figure in the lucrative genre of crime reporting. What makes Jack the Ripper singular is not what he did in the summer and fall of 1888 – it is what reporters did with him, and how their reporting impacted the medium in which the figure of the Ripper was created, developed, and disseminated: penny newspapers.

In the second half of 1888, the coverage of the brutal murders of prostitutes in Whitechapel demonstrated the growing profitability of crime reporting throughout the nineteenth century (Altick 3). Although Jack the Ripper is not “the first” or “the only,” he is extraordinary for the media sensation he inspired, and the influence Ripper reporting had on penny papers. Even in the midst of the terror, the murderer became an object of curious fascination, and in the absence of viable suspects, “the Ripper” was developed by periodicals that printed rumour and conjecture as much as supported facts, and even offered portraits of a person seen only by his victims. But as journalists gave shape to the looming figure of the Ripper, the reporting of his crimes and the subsequent investigations directly impacted the material structure of penny newspapers. Ripper reporting inspired shifts in column presentation, changes in the content and role of illustration, and impacted the rhetoric of newspaper advertising.

Though taking the Whitechapel Murders as its subject, this essay does not seek to engage in the game of “whodunnit” that saturates much of Ripperology; instead, it examines the textual materiality of sensational reporting as illustrated by coverage of Jack the Ripper – the inches given to, and placement of, other news items versus the placement and frequency of Whitechapel narratives, and advertising. Ultimately, this article seeks to build on Judith Walkowitz’s, Meghan Anwer’s, and L. Perry Curtis Jr.’s observations that the reporting of the Ripper’s crimes affirm cultural morals and class prejudices, and will argue that as Ripper reporting violently upset the body of the penny periodical, these publications artfully demonstrated their cultural perspectives and final deliberation on the morals of those involved, through advertisement and illustration.

This analysis is undertaken by an examination of three representative penny papers, two illustrated, beginning with the week of Martha Tabram’s violent death on 7 August, 1888, and continuing through the end of the year, a full month after the final Ripper victim was discovered. The earliest weeks provide a baseline for content, advertisement, and paper organization before the terror reached its narrative pinnacle, and the impact of Ripper reporting becomes most clear. It is the nature of sensational reporting to increase coverage as events escalate, and as Jack the Ripper continued to terrorize Whitechapel undetected, penny weeklies logically increased coverage. Reading this phenomenon, this paper marks the changes inspired by Ripper reporting, reading the rhetoric of artwork and advertisement, and demonstrating the material impact of sensational journalism.

Ripperologists have identified five women whose violent deaths they confidently attribute to the murderer known as Jack the Ripper. But in the autumn of terror, there was no such narrative, and far greater uncertainty in connecting murdered women to a single perpetrator. Because of both the closeness of time and the connections made by the press, I begin my research with the reporting of the death of Martha Tabram, a prostitute who was stabbed 39 times on 7 August, 1888. I also include the torso discovered on 3 October for similar reasons – both timing and the assertions made by the newspapers. To these I add the canonical five, who were murdered between 31 August and 9 November, 1888.

For its illustrations I examine Ripper reporting in The Illustrated Police News (Police News), and then a non-police illustrated periodical for comparison: The Penny Illustrated Paper (Penny Illustrated). Finally, to balance the use of illustration, I review Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (Lloyd’s), which illustrates only sparingly, focusing predominantly on textual narrative in reporting. All three publications are penny papers, offered on a weekly basis. To gain a scope of the papers both around and during the Ripper murders, I examine the full runs of all three from August through December, 1888.

Sensation in Print

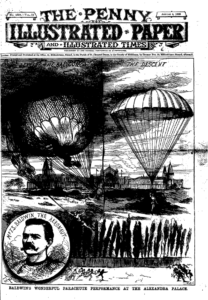

Figure 1: Cover of The Penny Illustrated Paper, 4 Aug. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,418, p. 65.

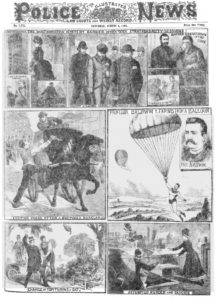

Though capitalizing on spectacle, penny papers did not exclusively trade in the salacious. On 4 and 5 August, 1888, Professor Baldwin’s daring leap from a balloon at the Alexandra palace was headline news. Lloyd’s describes the event in one-quarter of a front column, relating not just the thrill of the stunt, but its snags: the parachute caught in a tree during Baldwin’s descent, and it took the gentleman thirty minutes to walk back to the stage to meet his applause. The Police News, though specializing in crime reporting, prints an illustration of “Professor Baldwin Leaping From a Balloon,” including not only a graceful drawing of the man drifting to the ground as he hangs from his parachute by a single hand, but also a distinguished portrait detailing his respectable dress and impeccable moustache. The illustrations communicate an air of dignity and grace, holding Professor Baldwin as an exemplary figure of decorum and self-presentation even in this extraordinary act. The panel holds a place of significance on the front page, making up one-half of the centre third, neighbouring more pedestrian reports of an “Exciting Chase After a Supposed Burglar,” and topping the smaller panels of a gentleman tossing a feline – “Charge of Torturing a Cat” – and a woman leaping from a barge with an infant – “Attempted Murder and Suicide.” With its standard dedication to a single front page headliner (Figure 1), Penny Illustrated prints a sophisticated narrative illustration of the leap, using the Alexandra palace and neighbouring hedge as a single backdrop, while Baldwin dramatically “leaves the balloon” on the left, and majestically descended among rushing spectators on the right. His moustachioed portrait sits just above the caption “Baldwin’s wonderful Parachute Performance at the Alexandra Palace.” The event is an exhibition worthy of front-page illustration and attention, and Professor Baldwin is the man of the passing hour, but his notoriety was, predictably, not revisited in the following issues; the events, once reported, were no longer news, and Professor Baldwin was certainly not a sensation.

Though noteworthy as pieces of news, the headlines of 4 and 5 August are not sensational. Baldwin’s leap is a spectacle; with little to no social impact after it was accomplished it is a whole story, from leap to applause. The chase, cat-slinging, and attempted murder-suicide are consumable bites of gossip, but likewise offer no great impact for uninvolved readers – the reports are prosaic, with ready conclusions. Sensationalist reporting, such as that of the Whitechapel Murders, is a different reporting strategy altogether: inspiring investment in the process of developing story and suspense, it is a kind of serialized account that cannot project a conclusion, and thus captures public attention as it excites anxiety. Never sure what developments will come in the next day, reporters have the task of elevating the affective impact of each present paper edition, maintaining readerly interest by drawing out narratives even in the absence of factual development. Like serialized fiction, these accounts work to engage audiences through emotional involvement, securing present commercial value – the selling of this week’s paper – and future investments – the selling of the next – by peddling anxiety, shock, and curiosity. In the case of the Ripper, the violent, unidentified murderer promises a larger story to be told, but the sad histories of his victims prove a likewise valuable commodity.

Figure 2: Cover of The Illustrated Police News, 4 Aug. 1888, no. 1,277, p. 1.

In Deadly Encounters: Two Victorian Sensations (1986), Richard D. Altick argues that 1861 sees the dawning of sensation as a marketable journalistic approach with the reporting of two middle-class murders that feed “[t]he human desire to be shocked or thrilled, so long as whatever danger there was did not imminently affect the beholder” (3).[i] This narrative distance between reader and subject, achieved through moral reflection and public castigation, is essential to the burgeoning genre of sensational reporting as it frames these news stories not as entertainment, but lamentations of the failings of “others.” The cases themselves are (arguably) true, and the reporting of sordid details is then not blamed on the lurid imaginations of authors, but the moral weaknesses of individuals; likewise, the respectable reader of Victorian newspapers is encouraged to reflect on the failings of the subjects while taking comfort in their own moral superiority. These readers are protected from violent catastrophe because they assume such violent dealings are the natural consequence of illicit behaviour. This is especially significant in Ripper reporting, in no small part because the murder was targeting an unprotected, degraded, dehumanized class: women who were, or were believed to have been, prostitutes. As much as the question of the identity of the killer, the lives and misfortunes of the Ripper’s victims would come to be major subjects of consideration in contemporary periodicals.

Analysing crime reporting in Britain a hundred years after the Ripper murders, Moira Peelo and her co-authors provide a strong framework in “Newspaper Reporting and the Public Construction of Homicide” through which one can consider the commercial and cultural implications of Ripper reporting. They write: “reporting of crime is best understood as a part of defining ‘otherness’ and ‘difference’, rather than about debating issues of justice and equity,” and they observe that “newspapers pick out [cases] as exceptional or newsworthy [based] on an assessment of what is currently morally acceptable” (256). For their purposes, the researchers are faced with the task of identifying social definitions of morality, and through said definition, a further definition of homicide. While they acknowledge that “all homicides are shocking” they go on to assert that “society does not really believe killing to be wholly wrong on every occasion; or, at least, that every illegal killing is not always defined as homicide” (257, 258). Here, questions of both motive and victim become significant, allowing periodical readers to pardon and condemn murders as part of a system of cultural jurisprudence that affirms the readers’ moral sympathy or superiority, allowing them to act as judge and jury, and occasionally impacting the outcome of court proceedings through vociferous calls in the press itself (Knelman 31, 32).

Researching the sensational reporting of a tradesman’s bludgeoning of a gentleman on a train in 1864, Warren Fox speaks of Victorian newspapers’ justification of sensational reporting. Noting “an almost palpable defensiveness” for demonstrating interest in such ghoulish stories, Fox describes journalists’ attempts to frame narratives of murder as valuable to the reading public. In the reporting of such macabre proceedings, newspapers claimed to offer such benefits as “alerting the public to a danger to itself which the crime had exposed, questioning the practices of but [sic] ultimately restoring the public’s faith in its legal and judicial institutions, and educating the public on the character of its own society in contradistinction to the character of that most anti-social of social beings, the murderer” (272). In the absence of a suspect, however, newspapers offered readers another scapegoat, and the Ripper’s victims came under public scrutiny.

Of the confirmed victims of Jack the Ripper, the Daily Telegraph describes

women of middle age, [who] all were married and had lived apart from their husbands in consequence of intemperate habits, and were at the time of their death leading an irregular life, and eking out a miserable and precarious existence in common lodging houses. [The first four victims were] drunken, vicious, miserable wretches whom it was almost a charity to relieve of the penalty of existence, [and who were] not very particular about how they earned a living. (qtd. in Walkowitz 200)

These critical profiles were charged to direct the sympathies, and warn readers of the consequences of social deviance. That these women “live apart from their husbands” indicated fault on the part of the women, suggesting that they separated themselves from protective male figures who could have prevented their abuse. The women’s “irregular” lives indicated queerness of character, placing the victims outside of their moral places as mothers and housekeepers, and suggested that such “irregular” movements and occupations lead to their attacks. They were drunken and vicious, thus lamentable company and bad examples. Most extraordinary is the blatant statement that they were ultimately done a service in their violent murders, as reporters could not fathom wanting to continue such miserable lives. This description actively defined the immorality of the murder victims, and passed social judgment that suggested their deaths may be, if not acceptable punishment, then a consequence of their poor choices.

The Place of Things

“Trial by newspapers was a fact of Victorian life,” Richard Altick asserts (28), and in the reporting of their deaths the victims of Jack the Ripper were unapologetically dehumanized for their occupation; journalists constructed narratives to shift blame onto these women, and bolster the performative morality of both reporter and reader who uphold the social constructs of fidelity, chastity, and domesticity. In chapter seven of City of Dreadful Delights (1992), Judith Walkowitz describes the papers’ purposeful manipulation in the name of cultural morality. She observes, “Outside of Whitechapel, the victims became unsympathetic objects of pity,” for their occasional prostitution (201). Walkowitz asserts than an important matter of these texts is the condemnation of “women of evil life” (199). The criticism of these women, and less their murderer, can be seen in how the papers treat their textual placement in the body of the penny paper.

According to “Murder in Daily Installments,” penny weeklies appealed to working class reading publics who could not afford “a one-penny outlay for the newspaper six days a week,” and “approximately one-fourth to one-third of the content of these papers can be classified as sensational, that is, pertaining to ‘murder, crime and other thrilling events’” (Fox 273-4). To varying extents, these papers related news of import, cultural events for upwards aspirants, and sensational accounts of lovers murdering one another, violent robberies, and suicide attempts. On 11 and 12 August, 1888, both Lloyd’s and the Police News reported the violent death of Martha Tabram under the same title: “Tragedy in Whitechapel.” Despite the intended pathos of the title, the location of the articles demonstrates that this “tragedy” was no more remarkable than any other violent crime, and served a functional purpose as opposed to a culturally and socially significant one. The violence of the attack is extreme, Tabram was stabbed 39 times, but her death is marginally treated in the Police News on 11 August, 1888, occupying approximately two inches on the fourth and final page, beneath six inches of “The Alleged Frauds Upon Tradesman” and above three inches of “Lawlessness in Maybeolme.” Judith Flanders marks that the Daily News even goes so far as to report Tabram’s death as “a ‘supposed murder in Whitechapel’ – which since the woman had been stabbed more than three dozen times, seems to stretch the meaning of the word ‘supposed’ past breaking point” (425). The organisation of the Police News page, or rather the lack of organisation, is indicative of printing space being privileged over narrative, with page four stories arranged to balance longer and shorter articles, varying and limiting white space, and advertisements occupying the bottom of the fifth column and all of the sixth. The staccato language used in the reporting of Tabram’s assault, describing the body and injuries in the briefest language possible, supports a reading of the woman’s death as periodical mortar, noted for its violence over other crimes, but otherwise demonstrably unremarkable. The article reports that “Dr. Keeling, of Brick-lane … made an examination of the woman, and pronounced life extinct, giving it in his opinion that she had been brutally murdered, there being knife wounds on her breast, stomach, and abdomen” (“Tragedy in Whitechapel”). The assault is deemed “mysterious” not for its violence, but because “the woman is unknown, …. and no disturbance of any kind was heard during the night.” The article is a collection of facts – the length of the body, the time it is found, the colours of the woman’s clothing, the names of the five men attached to her discovery – but no story is offered.

Lloyd’s, made up of twelve sheets as compared to the Police News’s four, gave Tabram proportionally greater consideration, though the report is likewise placed innocuously, nestled among other police stories and occupying slightly less space than “The Chloroform Mystery” to the right. Here, though, greater commercial use was made of the story. Printed between pages of ads (6, 9-11), Lloyd’s gives the subtitle “A Woman stabbed in 39 places,” and prints ten names in reporting the discovery of the body, a technique used to sell papers through anecdotal connections. Penny Illustrated does not report Tabram’s death, instead running a number of core columns, including major theatrical productions (interestingly, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde), “Chat of the London Gossips,” and “Queen : Court : Fashion” (83). Penny Illustrated does include a column on “Life in the Courts,” reporting on criminals remanded, sentenced, and executed, but an unsolved murder of an occasional prostitute does not earn inches; as Judith Flanders observes, “The death of Martha Tabram aroused little interest, a common fate for these women, frequently alcoholic, all of them at the outer edges of poverty” (425). Tabram, like Professor Baldwin, is not sensational. By burying news of her death in later pages, Lloyd’s and the Police News have remarked on her cultural value: her death offers no great impact on the community at large, but may be of passing interest. Tabram’s headline is a useful mechanism to draw attention to pages that offer advertising revenue to the paper, but a dead prostitute is unlikely to sell papers if reported on the front page. This illustrates what I refer to as the “normal” state of these papers, reflecting editorial choices made outside of a sensational event. Tabram’s death is a mystery but hers is not yet a good story, and thus had no impact on the material structure of the paper. Her report fit on page four of the Police News, and so there she went. Penny Illustrated had no use for her at all. But by September 8, and Jack the Ripper’s second “canonical” kill, the case would be reported weekly in all three papers.

The layout of Penny Illustrated’s three-column page on 8 September, 1888 is instructive, articulating social priorities and buffering the sensationalism of “The Latest Murder of a Woman” with the reproduction of an item of intellectual curiosity and an advertisement for wholesome Dutch cocoa (Figure 3). In this page layout is an example of the “palpable defensiveness” noted by Fox (272): here, the murder is not a lurid and titillating headline, but a lamentable circumstance that happened separate from the space occupied by the reader. Immediately below the “Souvenir of the Egyptian Queen Makra” is the “The Whitechapel Mystery” report, which is illustrated by a woman’s hand snuffing a candle, as black birds, and what appears to be a broom, cross the moon. The identity of the arm’s owner, class, or marital status is unknown, reinforcing the article’s suggestion of both the potential of every-woman-ness in the unfortunate’s plight, but also this particular woman’s insignificance, as a disembodied hand takes the place of representation over her own portrait. The text of the article considers primarily the male perpetrator, the male physician who offers the pronouncement of death, and the estranged father who comes to identify the body.

Figure 3: Full page from The Penny Illustrated Paper, 8 Sept. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,423, p. 151.

The leading illustration of the Whitechapel article (Figure 3) is not the most prominent text on the page, prioritising instead the “Dutch Cocoa House” with a graphic that spans the width of two columns, sitting majestically in the centre of the page and materially disrupting the narrative of the murdered woman, which surrounds the cocoa house on three sides. The page strongly favours this charmingly domestic alternative, arguing that respectable citizens should remain informed of local events such as the Whitechapel “mystery” without becoming too

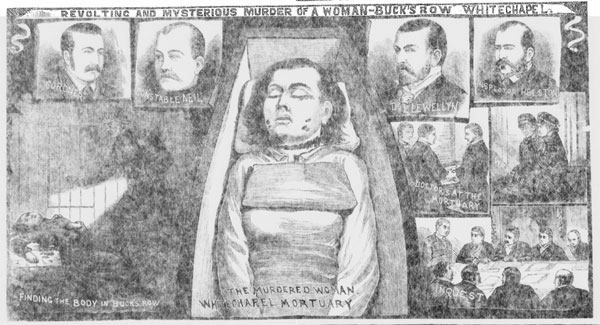

involved – it is a story for the moral to cluck over as they sip wholesome cocoa. Directly following news of the inquest regarding the discovery of “the poor woman’s body,” the text identifies her corpse as a curiosity to be seen, not a person to be mourned or a crime to overly-concern good, moral citizens. The juxtaposition focuses blame on the victim, associated with “the squalid districts of the East-End” and “some of the lowest types of humanity to be found in any capital [where] drunkenness is rife,” and instead urges its readers towards the “temperance” advertised by the cocoa-house. On the same day, 8 September, 1888, the Police News publishes on its front page a ghoulish portrait of the victim laid out in a casket, surrounded by portraits of men attached to the case (Figure 4). Here the victim is not an “everywoman,” but a tangible object pinned down by the text in the moment of her death – she is “the body” found in Buck’s row, and “the murdered woman” occupying a casket, wounds visible, who has become the responsibility of the seventeen male professionals illustrated in the frame. The readers are invited into their thoughtful midst to consider the condition of this central object, focusing not on the person she was, but the violence she represents (Police News, “Revolting and Mysterious Murder of a Woman – Buck’s Row Whitechapel”).

Figure 4: Centre panel of The Illustrated Police News, 8 Sept. 1888, no. 1,282, p. 1.

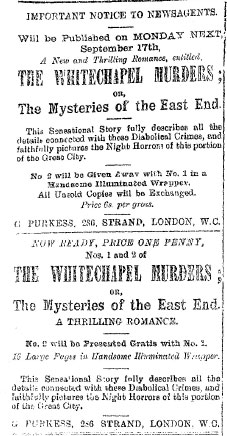

As Jack the Ripper continued to terrorize Whitechapel, penny weeklies responded by extending coverage, and advertisement revenue: both the Police News and Lloyd’s increased the number of advertisements, without expanding the full length of the publication. In this way, sensational Ripper reporting becomes a material usurper in the body of the penny paper: as panic (and social investment) grows, so do the Ripper’s column inches, displacing other headlines and overwhelming front pages with macabre inquest accounts, pathetic biographies, and outlandish theories. The textual abrasion of newspaper content – the aggressiveness intended to draw attention through coarse content – is not limited to this front-page assault, but rather influences the cannibalizing of internal reporting space for the sake of further capitalization: advertisements begin taking up inches previously used for reporting other events, such as the stabbing of Martha Tabram. Between 4 and 12 August, advertisements, largely for quack medications, family medical journals, and cheap sensational literature, take up a rough average of fourteen inches in the Police News, and seventeen columns in Lloyd’s. By 6 and 7 October, as five victims were attributed to Ripper, and the “Saucy Jack” postcard was reprinted in the Star,[i] these estimates increase to thirty-two inches in the Police News and twenty-one columns in Lloyd’s. This increase suggests that advertisers were as keen to profit from the public interest in Jack the Ripper as the papers themselves, and recognised that close material association with Ripper reporting increased product exposure. Like the actual real estate of Whitechapel, which continues to draw murder tourists seeking a thrill and connection to the real-time drama of the murders, the real estate of the penny papers increased in value for being seen, whether one was selling a tonic for colicky babies or a penny blood titled “The Whitechapel Murders; or The Mysteries of the East End” (Figure 5). Such products affirmed editorial decisions to increase coverage and extend revenue, and encouraged the symbiotic relationship of sensational reporting and advertisement.

Figure 5: Advertisement from The Illustrated Police News, 15 Sept. 1888, no. 1,283, p. 4.

Other curious advertisements share the Ripper’s space in Penny Illustrated, including a “Curative Electricity Harness” for nervous complaints on 15 September, a request for railway servants on 22 September, remedies to overcome weakness and vitality, and an invention to guarantee success – “Fruit Salt” (214) – when Ripper sensation is at its peak, on 6 October. Most poignant, though, is an advertisement that appears on several dates, and on 6 October is situated at the bottom of a column disclosing the discovery of a woman’s torso: Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup (Figure 6). The advert, “Advice to Mothers,” details “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup,” a miracle drug that is “perfectly harmless” and promises to cure babies of all teething and colicky complaints. The placement and language are purposeful, and communicate expectations of readership. On 13 October, the advert runs directly below the reporting of the inquest of the nameless torso, its proximity speaking to the expected audience of this ghastly news: women consumers. Despite the concern of authorities, who saw fit to clear the courtroom “of women and boys before Dr Phillips gave his evidence” on the autopsy of Mrs. Chapman (Flanders 433), penny papers recognised that sensational stories had household appeal, and women read of the rippings just as men did. The market is extensive. But the juxtaposition of inquest report and household advertising is not entirely supportive of female readership, as the violence of the report counters the domesticity of the product, and speaks to the gendered judgement of the victims noted by Walkowitz (200-1): here is a subtle warning to women against the poor choices made by the victims of Jack the Ripper. The material placement creates a parallel course for women: on one path they may find security and domestic fulfilment, but on the other a lack of protection and violent death. Readers may face the threat of the Ripper if they entertain the notion of leaving their domestic roles, and must instead seek security in social order, domesticity, and, perhaps, Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup.

Figure 6: Column from The Penny Illustrated Paper, 6 Oct 1888, vol. 55, no. 1427, p.215.

The Face of Things

The most significant aspect of any newspaper advertisement is the front cover itself; the layout, illustrations and headlines are intended to appeal to audiences and lure them into the commercial exchange of murder for a penny. As early as 18 August, the Whitechapel mysteries were featured on the cover of the Police News (“The Horrible and Mysterious Murder at George’s Yard, Whitechapel Road”); Lloyd’s followed suit with a leading article on 2 September (“The Whitechapel Horror”), and Penny Illustrated makes up for lost time on 13 October with a full-page front illustration of the funeral of Catherine Eddowes, who was murdered forty-five minutes after Elizabeth Stride on 30 September, 1888 (“Sketches in Connection with the Whitechapel and Aldgate Murders”).

Including few illustrations overall, and no cover art, the frontal advertising of Lloyd’s is communicated by inches and headlines. On 2 September, a front-and-centre column headline promises “White Chapel Horror: A Sad Family History Disclosed,” staging the murder as a domestic tragedy from a poor neighbourhood. Though itself a top headline, Whitechapel contests with “Irish Facts and Fictions,” “Yesterday’s Telegrams,” “Serious Shipping Disasters,” and “Last Night’s Theatricals”; as three of the five columns begin with news of foreign affairs, Whitechapel becomes most closely aligned with the Haymarket theatricals, casting the murder as an entertaining domestic spectacle.

The next week, Whitechapel retains its position in Lloyd’s, but doubles in inches (“Yesterday’s Whitechapel Tragedy”), and by 16 September, following the gruesome murders of Martha Tabram, Polly Nichols, and Annie Chapman, Lloyd’s lets the whole first column, and nearly all of the third, to Ripper reporting, fencing the middle column with telegrams and “Kindness and its reward” (“The Whitechapel Murders”). At its height, Whitechapel occupies thirty-nine inches – two and three-quarter columns – of the cover, and three whole central columns on page seven. Here, on 7 October (“The East End Tragedies”), the most recent edition after the discovery of the torso, Lloyd’s includes three images: a “sketch of Mitre-square” with a convenient “x” showing the place where the Ripper left Eddowes (“The East-End Murders”), “Aldgate Tragedy: Sketch of the City Coroner’s Court” featuring portraits of “The Coroner,” “Lodging House Keeper,” “Kelly,” “Police Constable Watkins,” and “Dr. Gordon Brown” floating around a large galley of thirty-seven men and one female witness, and “The Locality of the Murders.” This last, a map, neatly labels the locations where the Ripper’s victims are found, and names each woman (Smith, Tabram, Nicholls, Chapman, Stride, and Eddowes) by corresponding number.

The purpose of breaking form and including illustrations – particularly murder maps – is pointed: Lloyd’s was leading the way in providing a valuable guidebook for the curious, and encouraged readers to indulge their interest in murder tourism. That the paper sanctions these excursions while the murderer is still active speaks to the cultural status of the Whitechapel Victims. “The murdered women were objects of fantasy for residents of Whitechapel as well as for the educated reading public” (216), Walkowitz observes, but their slaying carries a narrative of victim shaming developed in the penny papers. By directing readers, Lloyd’s suggests that they may visit the killing grounds in safety, enjoying a thrill, while protected by respectability. Prostitutes beware, but all others may pass.

Attempting to preserve a tone of decorum, while capitalising on the frenzy that is caused by the Ripper murders, Penny Illustrated established a tone of respectful mourning on 13 October with its cover illustration of a funeral procession;[i] hovering above in a perfectly circular frame is a flattering portrait of a demure “Kate Eddowes,” and looming over her shoulder, a ragged sheet containing a “Sketch of the Man Who Visited Mr. Lusk” (“Sketches in Connection with the Whitechapel and Aldgate Murders”). The cover of the 17 November edition focuses, like Lloyd’s, on geography, representing three street scenes and ambulatory residents – places instead of remains, focusing on what any reader may experience (“The Miller-Court Murder, Whitechapel: Site of Mary Kelly’s Lodgings”). Interior sketches on 6 October are similarly preoccupied with representations of the public and the social; the closest depictions of corpses are the sheet-draped figure on page 212, and a poor sketch of a woman on a mortuary table, covered to the chin as if in bed, on page 213 (“Scenes of the Aldgate and Whitechapel Murders”). Bodies, Penny Illustrated projected, are repulsive, and they favoured public consciousness, tempering colourful language with reserved images, performing moral dignity by avoiding debasement of sensational illustration, while still guiding audiences through the spectacle.

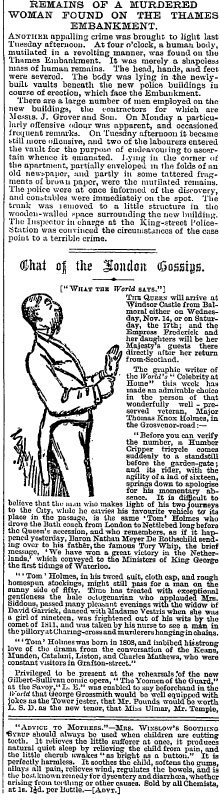

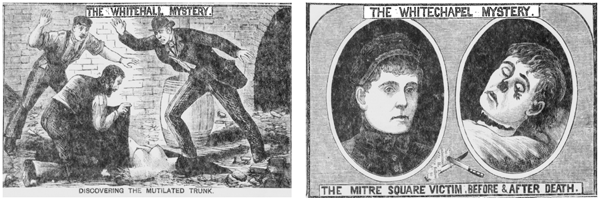

Figures 7 and 8: Panels from The Illustrated Police News, 13 Oct. 1888, no. 1,287, p. 1.

With no such compunctions for dignity, the Police News represented all victims as they sprawled in the streets, with nervous men hovering above, aghast (Figure 7, “Discovering the Mutilated Trunk”). Each victim was explicitly illustrated in the moment of discovery: pairs of victim portraits – living and dead – were deemed essential, the better to emphasise the horror of their fall (Figure 8, “The Mitre Square Victim, Before and After Death”). Commanding part of nearly every cover from 11 August through 8 December, Ripper-related illustrations occupied one-third of the cover on 18 August, and 8 and 29 September; they made up half of the page on 3 and 24 November, and 1 and 8 December; two-thirds were Ripper victims on 15 and 22 September, and 27 October; and full page crime narratives were presented in vivid detail, presenting a blood-soaked roadmap of mutilation, on 6, 13 and 20 October, and 17 November. The major players, suspects, victims’ bodies, and locations are clearly labelled, portraits revealing missing noses, bruises, and lacerations. They become dehumanized things, their living portraits suggesting they had the potential to live better lives, but behaved poorly and met violent consequences (and were thus ultimately remembered in mortuary sketches). In the absence of mortuary photographs, periodical illustrations are the closest material link the reading public had to the Ripper case. By incorporating portraits, maps, and inquest landscapes, the newspapers established a tourist guide, through which the reader could examine and explore the seedy shadows of Whitechapel, and the ghastly consequences of the immoral lives of prostitutes.

Figure 9: Headline of The Illustrated Police News, 23 Apr. 1887, no. 1,210, p. 1.

This content is not unique to Ripper reporting. In April of 1887, the Police News reported on a triple French homicide, with similar attention to gory detail (“Horrible Triple Murder in Paris – Portraits of the Three Women (from Photos)”). The accompanying illustrations unapologetically rendered the three women with their heads nearly – or fully, in the case of the twelve-year-old girl – removed (Figure 9). It is tempting to suggest that the Police News treated their British prostitutes with a modicum more decency than these French victims, but an examination of the structure of the paper shows that this was not the case. The violence of the illustrations of Regnault and the Gremerets was shocking, but offered no commentary on the victims themselves; they were dehumanized in this moment, but in the isolation of these illustrations became something separate from the victims themselves. But by placing living portraits of Whitechapel victims on a paper cover with mortuary illustrations and crime scene guides, the Police News casts the memories of the living women as only future Ripper targets. They were frozen in the moment of their attack, and reduced to the extent that they could be nothing else. The living women were absorbed by the news narrative, and so they became known not as individuals, loved ones, impoverished women struggling in a social system that condemned them, but only drunken prostitutes who left their husbands and were then slaughtered like animals. The fetishisation of these women reached an apex with the mid-October discovery of the dismembered body.

The bare breasts of this victim were put on vivid display by the Police News (Figure 7) first on 13 October, and then on 20 October, when an arm was being fitted (Figure 10, “Sketches of the Whitehall Mystery”). In each illustration, three men observe the form, whose pubis is discretely covered with draped cloth. The shapeliness of the breasts, the feminine profile of the mortuary cart, and the artistic angles invite voyeurism, allowing unabashed fetishism for all the Ripper victims through this unknown, and objectified, “trunk.” She is an “ideal” victim for reporting, open for the heteronormative gaze, and unburdened by narratives of husbands, sons, and fathers, and represented the culmination of the violence of the Ripper narrative.

Figure 10: Two panels from The Illustrated Police News, 20 October, 1888, no. 1288, p. 1.

The illustrations in the Police News demonstrated a clear ignorance of the mortuary photographs of Catherine Eddowes, whose jagged incision and sunken breasts invoke the monstrous rather than the illicit. These illustrations sexualize the crime, while blaming sex for the murders.

In the case of the Ripper mortuary photographs, the images attest to the obliterative “artistic” might and agency of the Ripper, while also acknowledging the technical prowess of medical personnel, the doctors and coroners engaged, with just as much skill as the Ripper, in reassembling these dismembered and mutilated female bodies. (Anwer 436)

The photographs themselves told a far more pitiful story. The mortuary and crime scene photos of Catherine Eddowes and Mary Kelly are achingly human. These final images represent the last material texts of Eddowes and Kelly, who, thanks to the efforts of Ripper, the police, and the press, are reduced to objects reflecting their occupation and the violent actions taken against them, and not the complete women they were.

By 25 November neither Lloyd’s nor the Penny Illustrated are reporting on the Ripper, and the murders are not recounted again after the 22 December edition of the Police News. Jack the Ripper had never been conclusively identified, and though papers would resurrect his character in connection to some future violent crimes, public interest waned by the Christmas editions, and the media phenomenon had passed for most periodicals. However, the materiality of the texts remain, and the pages of the penny weeklies continue to relate clues, give life to theories, and tyrannically typecast the women who fell under the knife in the “autumn of terror,” 1888.

Conclusion

The Victorian serial killer known as “Jack the Ripper” did not exist: he was a fabrication of sensationalist journalism, used successfully to market the narrative of murdered women in a poor neighbourhood in 1888 London. This is not to suggest a conspiracy theory of any sort – a murderer or associated murderers did exist, and violently ended the lives of at least Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. The name, occupation, gender, or even number of killers remains inconclusive. But the character of Jack the Ripper was good for business for penny papers, and he was, as the public knew him, a product of those papers. The infamous 29 September correspondence that began “Dear Boss” and named the murderer for the first time – his “trade name” – was “almost certainly written by journalists” (Flanders 36). With license, illustrators were able to craft a monster of a man befitting his crimes, the surrealism of the drawings allowed by a suspension of disbelief rooted in his perpetual evasion. None of these elements have been conclusively determined, but the figure of the Ripper, imagined by these publications, was a lucrative advertising campaign.

The gainful occupation of Ripper reporting materially impacted the penny weeklies that evolved to accommodate, and thus profit from, this sensational story. In August of 1888, “minor” criminal reports such as the stabbing of Martha Tabram found public recognition, if only on the back page of a Police News; by September such stories were ignored, in order for papers to profit from the interest of the public in Jack the Ripper, and advertisers anxious to capture readers’ attention. The structure of the paper shifted, and “smaller” stories were forsaken in order to accommodate advertising inches, as the Ripper became the main subject of reporting to the detriment of other goings-on. Papers such as Lloyd’s changed design to meet the demands of Ripper interest, not only introducing illustration, but providing readers with detailed maps of the streets where the women met violent ends, the better for those readers to retrace their steps. These papers, in large, became less weekly news sheets, and more frequently guides to the continued consumption of the mystery and violence of the Whitechapel Murders.

Most marked, however, is the ways in which penny weeklies used the material structure of the papers to communicate and uphold social values. The Police News, Lloyd’s, and Penny Illustrated constructed secondary narratives of judgement on the women who lost their lives, objectifying them in their deaths, dehumanizing their experiences, and offering readers commercial alternatives and social direction. The Ripper escaped detection by police and the press, but his victims were brutalized twice: first by the Ripper, and then the Victorian press. They were ultimately sold as moral anecdotes to uphold middle-class gender values. In the end they were exploited as attractions to increase commerce in weekly papers, penny dreadfuls, and Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup alike.

Notes

[i] The cover from 6 October carries the caption “London’s Reign of Terror: Scenes of Sunday Morning’s Murders in the East-End,” but the illustration is so saturated in black it cannot be deciphered.

[i] The card read: “I was not codding dear old Boss when I gave you the tip, you’ll hear about Saucy Jack’s work tomorrow double event this time number one squealed a bit couldn’t finish straight off. Had not got time to get ears off for police thanks for keeping last letter back till I got to work again. Jack the Ripper.” Letters and postcards from correspondents claiming to be the murderer were numerous, and most were dismissed by police. The “Saucy Jack” postcard contained enough detail that police believed the murderer could have sent it, but this was never confirmed.

[i] The two cases Altick considers from 1861 are the “Northumberland Street affair,” involving an Army major, his mistress, and the violent death of a moneylender, and the case of a French nobleman named Vidil, who attempted to murder his son over the son’s inheritance.

[i] FBI agent Robert Ressler coined the term “serial killer” in 1974, 101 years after the death of Mary Ann Cotton (Bonn). Thus, neither Cotton nor Jack the Ripper would be called “serial killers” by their Victorian contemporaries.

List of Illustrations

Figure 1: Cover of The Penny Illustrated Paper, 4 Aug. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,418, p. 65.

Figure 2: Cover of The Illustrated Police News, 4 Aug. 1888, no. 1,277, p. 1.

Figure 3: Full page from The Penny Illustrated Paper, 8 Sept. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,423, p. 151.

Figure 4: Centre panel of The Illustrated Police News, 8 Sept. 1888, no. 1,282, p. 1.

Figure 5: Advertisement from The Illustrated Police News, 15 Sept. 1888, no. 1,283, p. 4.

Figure 6: Column from The Penny Illustrated Paper, 6 Oct 1888, vol. 55, no. 1427, p. 215.

Figure 7: Panel from The Illustrated Police News, 13 Oct. 1888, no. 1,287, p. 1.

Figure 8: Panel from The Illustrated Police News, 13 Oct. 1888, no. 1,287, p. 1.

Figure 9: Headline of The Illustrated Police News, 23 Apr. 1887, no. 1,210, p. 1.

Figure 10: Two panels from The Illustrated Police News, 20 October, 1888, no. 1288, p. 1.

Bibliography

Altick, Richard D. Deadly Encounters: Two Victorian Sensations. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986.

Anwer, Meghan. “Murder in Black and White: Victorian Crime Scenes and the Ripper Photographs.” Victorian Studies, vol. 56, no. 3, 2014, pp. 433-41.

Bonn, Scott A. “Origin of the Term ‘Serial Killer.’” Psychology Today, 9 June 2014, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/wicked-deeds/201406/origin-the-term-serial- killer. Accessed 30 July 2018.

Curtis, L. Perry Jr. Jack the Ripper and the London Press. Yale University Press, 2001.

Flanders, Judith. The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime. Thomas Dunne Books, 2011.

Fox, Warren. “Murder in Daily Instalments: The Newspapers and the Case of Franz

Müller (1864).” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 31, no. 3, 1998, pp. 271-98.

The Illustrated Police News. “Horrible Tripe Murder in Paris – Portraits of the Three Women (from Photos).” 23 April 1887, no. 1,210, p. 1. British Newspapers 1600-1950.

The Illustrated Police News. August – December 1888. British Newspapers 1600-1950.

—. “The Alleged Frauds Upon Tradesman.” 11 Aug. 1888, no. 1278, p. 4.

—. “Attempted Murder and Suicide.” 4 Aug. 1888, no. 1,277, p. 1.

—. “Charge of Torturing a Cat.” 4 Aug. 1888, no. 1,277, p. 1.

—. “Discovering the Mutilated Trunk.” 13 Oct. 1888, no. 1,287, p. 1.

—. “Exciting Chase After a Supposed Burglar.” 4 Aug. 1888, no. 1,277, p. 1.

—. “The Horrible and Mysterious Murder at George’s Yard, Whitechapel Road.” 18 Aug. 1888, no. 1,279, p. 1.

—. “Horrible Triple Murder in Paris – Portraits of the Three Women (from Photos).” 23 April 1887, no. 1,210, p. 1.

—. “Important Notice to Newsagents.” 15 Sept. 1888, no. 1,283, p. 4.

—. “Lawlessness in Maybeolme.” 11 Aug. 1888, no. 1,278, p. 4.

—. “The Mitre Square Victim, Before and After Death.” 13 Oct. 1888, no. 1,287, p. 1.

—. “Professor Baldwin Leaping from a Balloon.” 4 Aug. 1888, no. 1,277, p. 1.

—. “Revolting and Mysterious Murder of a Woman – Buck’s Row Whitechapel.” 8 Sept. 1888, no. 1,282, p. 1.

—. “Sketches of the Whitehall Mystery.” 20 Oct. 1888, no. 1288, p. 1.

—. “Tragedy in Whitechapel.” 11 Aug. 1888, no. 1278, p. 4.

Knelman, Judith. “Class and Gender Bias in Victorian Newspapers.” Victorian

Periodicals Review, vol. 26, no.1, 1993, pp. 29-35.

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper. August-December1888. British Newspapers 1600-1950.

—. “Aldgate Tragedy: Sketch of the City Coroner’s Court.” 7 Oct. 1888, no. 2,394, p. 7.

—. “The Chloroform Mystery.” 12 Aug. 1888, no. 2,386, p. 7.

—. “The East-End Murders.” 7 Oct. 1888, no. 2,394, p. 7.

—. “The East-End Tragedies.” 7 Oct. 1888, no. 2,394, p. 1.

—. “The Locality of the Murders.” 7 Oct. 1888, no. 2,394, p. 7.

—. “More Exciting Balloon Leap.” 5 Aug. 1888, no. 2,385, p. 1.

—. “Tragedy in Whitechapel.” 12 Aug. 1888, no. 2,386, p. 7.

—. “The Whitechapel Murders.” 16 Sept. 1888, no. 2391, p. 1.

—. “The Whitechapel Horror.” 2 Sept. 1888, no. 2,390, p. 1.

—. “Yesterday’s Whitechapel Tragedy.” 9 Sept. 1888, no. 2,390, p. 1.

McLaren, Angus. A Prescription for Murder: The Victorian Serial Killings of Dr. Thomas Neil Cream. University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Peelo, Moira, et al. “Newspaper Reporting and the Public Construction of Homicide.” The British Journal of Criminology, vol. 44, no. 3, 2004, pp. 256-275.

The Penny Illustrated Paper. 4 August 1888. British Newspapers 1600-1950.

—. “Advice to Mothers.” 6 Oct 1888, vol. 55, no. 1427, p. 215.

—. “Baldwin’s wonderful Parachute Performance at the Alexandra Palace.” 4 Aug. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,418, p. 65.

—. “Dutch Cocoa-House.” 8 Sept. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,423, p. 151.

—. “Life in the Courts.” 11 Aug. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,419, p. 87.

—. “The Miller-Court Murder, Whitechapel: Site of Mary Kelly’s Lodgings.” 17 Nov. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,433, p. 305.

—. “Queen: Court: Fashion.” 11 Aug. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,419, p. 83.

—. “Scenes of the Aldgate and Whitechapel Murders.” 6 Oct 1888, vol. 55, no. 1427, p. 212.

—. “Sketches in Connection with the Whitechapel and Aldgate Murders.” 13 Oct. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,428, p. 225.

—. “Souvenir of the Egyptian Queen Makra.” 8 Sept. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,423, p. 151

—. “The Whitechapel Mystery.” 8 Sept. 1888, vol. 55, no. 1,423, p. 151.

Walkowitz, Judith R. City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-

Victorian London. University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Worsley, Lucy. The Art of the English Murder. Pegasus Books, 2014.